[ad_1]

Form of shared Internet-based computing

Cloud computing[1] is the on-demand availability of computer system resources, especially data storage (cloud storage) and computing power, without direct active management by the user.[2] Large clouds often have functions distributed over multiple locations, each of which is a data center. Cloud computing relies on sharing of resources to achieve coherence and typically uses a “pay as you go” model, which can help in reducing capital expenses but may also lead to unexpected operating expenses for users.[3]

Value proposition[edit]

Advocates of public and hybrid clouds claim that cloud computing allows companies to avoid or minimize up-front IT infrastructure costs. Proponents also claim that cloud computing allows enterprises to get their applications up and running faster, with improved manageability and less maintenance, and that it enables IT teams to more rapidly adjust resources to meet fluctuating and unpredictable demand,[4][5][6] providing burst computing capability: high computing power at certain periods of peak demand.[7]

According to IDC, the global spending on cloud computing services has reached $706 billion and expected to reach $1.3 trillion by 2025.[8] While Gartner estimated that the global public cloud services end-user spending forecast to reach $600 billion by 2023.[9] As per McKinsey & Company report, cloud cost-optimization levers and value-oriented business use cases foresees more than $1 trillion in run-rate EBITDA across Fortune 500 companies as up for grabs in 2030.[10] In 2022, more than $1.3 trillion in enterprise IT spending is at stake from the shift to cloud, growing to almost $1.8 trillion in 2025, according to Gartner.[11]

History[edit]

The term cloud was used to refer to platforms for distributed computing as early as 1993, when Apple spin-off General Magic and AT&T used it in describing their (paired) Telescript and Personal Link technologies.[12] In Wired’s April 1994 feature “Bill and Andy’s Excellent Adventure II”, Andy Hertzfeld commented on Telescript, General Magic’s distributed programming language:

“The beauty of Telescript … is that now, instead of just having a device to program, we now have the entire Cloud out there, where a single program can go and travel to many different sources of information and create a sort of a virtual service. No one had conceived that before. The example Jim White [the designer of Telescript, X.400 and ASN.1] uses now is a date-arranging service where a software agent goes to the flower store and orders flowers and then goes to the ticket shop and gets the tickets for the show, and everything is communicated to both parties.”[13]

Early history[edit]

During the 1960s, the initial concepts of time-sharing became popularized via RJE (Remote Job Entry);[14] this terminology was mostly associated with large vendors such as IBM and DEC. Full-time-sharing solutions were available by the early 1970s on such platforms as Multics (on GE hardware), Cambridge CTSS, and the earliest UNIX ports (on DEC hardware). Yet, the “data center” model where users submitted jobs to operators to run on IBM’s mainframes was overwhelmingly predominant.

In the 1990s, telecommunications companies, who previously offered primarily dedicated point-to-point data circuits, began offering virtual private network (VPN) services with comparable quality of service, but at a lower cost. By switching traffic as they saw fit to balance server use, they could use overall network bandwidth more effectively.[citation needed] They began to use the cloud symbol to denote the demarcation point between what the provider was responsible for and what users were responsible for. Cloud computing extended this boundary to cover all servers as well as the network infrastructure.[15] As computers became more diffused, scientists and technologists explored ways to make large-scale computing power available to more users through time-sharing.[citation needed] They experimented with algorithms to optimize the infrastructure, platform, and applications, to prioritize tasks to be executed by CPUs, and to increase efficiency for end users.[16]

The use of the cloud metaphor for virtualized services dates at least to General Magic in 1994, where it was used to describe the universe of “places” that mobile agents in the Telescript environment could go. As described by Andy Hertzfeld:

“The beauty of Telescript,” says Andy, “is that now, instead of just having a device to program, we now have the entire Cloud out there, where a single program can go and travel to many different sources of information and create a sort of a virtual service.”[17]

The use of the cloud metaphor is credited to General Magic communications employee David Hoffman, based on long-standing use in networking and telecom. In addition to use by General Magic itself, it was also used in promoting AT&T’s associated Personal Link Services.[18]

2000s[edit]

In July 2002, Amazon created subsidiary Amazon Web Services, with the goal to “enable developers to build innovative and entrepreneurial applications on their own.” In March 2006 Amazon introduced its Simple Storage Service (S3), followed by Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) in August of the same year.[19][20] These products pioneered the usage of server virtualization to deliver IaaS at a cheaper and on-demand pricing basis.

In April 2008, Google released the beta version of Google App Engine.[21] The App Engine was a PaaS (one of the first of its kind) which provided fully maintained infrastructure and a deployment platform for users to create web applications using common languages/technologies such as Python, Node.js and PHP. The goal was to eliminate the need for some administrative tasks typical of an IaaS model, while creating a platform where users could easily deploy such applications and scale them to demand.[22]

In early 2008, NASA’s Nebula,[23] enhanced in the RESERVOIR European Commission-funded project, became the first open-source software for deploying private and hybrid clouds, and for the federation of clouds.[24]

By mid-2008, Gartner saw an opportunity for cloud computing “to shape the relationship among consumers of IT services, those who use IT services and those who sell them”[25] and observed that “organizations are switching from company-owned hardware and software assets to per-use service-based models” so that the “projected shift to computing … will result in dramatic growth in IT products in some areas and significant reductions in other areas.”[26]

In 2008, the U.S. National Science Foundation began the Cluster Exploratory program to fund academic research using Google-IBM cluster technology to analyze massive amounts of data.[27]

In 2009, the government of France announced Project Andromède to create a “sovereign cloud” or national cloud computing, with the government to spend €285 million.[28][29] The initiative failed badly and Cloudwatt was shut down on 1 February 2020.[30][31]

2010s[edit]

In February 2010, Microsoft released Microsoft Azure, which was announced in October 2008.[32]

In July 2010, Rackspace Hosting and NASA jointly launched an open-source cloud-software initiative known as OpenStack. The OpenStack project intended to help organizations offering cloud-computing services running on standard hardware. The early code came from NASA’s Nebula platform as well as from Rackspace’s Cloud Files platform. As an open-source offering and along with other open-source solutions such as CloudStack, Ganeti, and OpenNebula, it has attracted attention by several key communities. Several studies aim at comparing these open source offerings based on a set of criteria.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39]

On March 1, 2011, IBM announced the IBM SmartCloud framework to support Smarter Planet.[40] Among the various components of the Smarter Computing foundation, cloud computing is a critical part. On June 7, 2012, Oracle announced the Oracle Cloud.[41] This cloud offering is poised to be the first to provide users with access to an integrated set of IT solutions, including the Applications (SaaS), Platform (PaaS), and Infrastructure (IaaS) layers.[42][43][44]

In May 2012, Google Compute Engine was released in preview, before being rolled out into General Availability in December 2013.[45]

In 2019, Linux was the most common OS used on Microsoft Azure.[46] In December 2019, Amazon announced AWS Outposts, which is a fully managed service that extends AWS infrastructure, AWS services, APIs, and tools to virtually any customer datacenter, co-location space, or on-premises facility for a truly consistent hybrid experience.[47]

Similar concepts[edit]

The goal of cloud computing is to allow users to take benefit from all of these technologies, without the need for deep knowledge about or expertise with each one of them. The cloud aims to cut costs and helps the users focus on their core business instead of being impeded by IT obstacles.[48] The main enabling technology for cloud computing is virtualization. Virtualization software separates a physical computing device into one or more “virtual” devices, each of which can be easily used and managed to perform computing tasks. With operating system–level virtualization essentially creating a scalable system of multiple independent computing devices, idle computing resources can be allocated and used more efficiently. Virtualization provides the agility required to speed up IT operations and reduces cost by increasing infrastructure utilization. Autonomic computing automates the process through which the user can provision resources on-demand. By minimizing user involvement, automation speeds up the process, reduces labor costs and reduces the possibility of human errors.[48]

Cloud computing uses concepts from utility computing to provide metrics for the services used. Cloud computing attempts to address QoS (quality of service) and reliability problems of other grid computing models.[48]

Cloud computing shares characteristics with:

- Client–server model—Client–server computing refers broadly to any distributed application that distinguishes between service providers (servers) and service requestors (clients).[49]

- Computer bureau—A service bureau providing computer services, particularly from the 1960s to 1980s.

- Grid computing—A form of distributed and parallel computing, whereby a ‘super and virtual computer’ is composed of a cluster of networked, loosely coupled computers acting in concert to perform very large tasks.

- Fog computing—Distributed computing paradigm that provides data, compute, storage and application services closer to the client or near-user edge devices, such as network routers. Furthermore, fog computing handles data at the network level, on smart devices and on the end-user client-side (e.g. mobile devices), instead of sending data to a remote location for processing.

- Utility computing—The “packaging of computing resources, such as computation and storage, as a metered service similar to a traditional public utility, such as electricity.”[50][51]

- Peer-to-peer—A distributed architecture without the need for central coordination. Participants are both suppliers and consumers of resources (in contrast to the traditional client-server model).

- Cloud sandbox—A live, isolated computer environment in which a program, code or file can run without affecting the application in which it runs.

Characteristics[edit]

Cloud computing exhibits the following key characteristics:

- Cost reductions are claimed by cloud providers. A public-cloud delivery model converts capital expenditures (e.g., buying servers) to operational expenditure.[52] This purportedly lowers barriers to entry, as infrastructure is typically provided by a third party and need not be purchased for one-time or infrequent intensive computing tasks. Pricing on a utility computing basis is “fine-grained”, with usage-based billing options. As well, less in-house IT skills are required for implementation of projects that use cloud computing.[53] The e-FISCAL project’s state-of-the-art repository[54] contains several articles looking into cost aspects in more detail, most of them concluding that costs savings depend on the type of activities supported and the type of infrastructure available in-house.

- Device and location independence[55] enable users to access systems using a web browser regardless of their location or what device they use (e.g., PC, mobile phone). As infrastructure is off-site (typically provided by a third-party) and accessed via the Internet, users can connect to it from anywhere.[53]

- Maintenance of cloud environment is easier because the data is hosted on an outside server maintained by a provider without the need to invest in data center hardware. IT maintenance of cloud computing is managed and updated by the cloud provider’s IT maintenance team which reduces cloud computing costs compared with on-premises data centers.

- Multitenancy enables sharing of resources and costs across a large pool of users thus allowing for:

- centralization of infrastructure in locations with lower costs (such as real estate, electricity, etc.)

- peak-load capacity increases (users need not engineer and pay for the resources and equipment to meet their highest possible load-levels)

- utilization and efficiency improvements for systems that are often only 10–20% utilized.[56][57]

- Performance is monitored by IT experts from the service provider, and consistent and loosely coupled architectures are constructed using web services as the system interface.[53][58]

- Productivity may be increased when multiple users can work on the same data simultaneously, rather than waiting for it to be saved and emailed. Time may be saved as information does not need to be re-entered when fields are matched, nor do users need to install application software upgrades to their computer.

- Availability improves with the use of multiple redundant sites, which makes well-designed cloud computing suitable for business continuity and disaster recovery.[59]

- Scalability and elasticity via dynamic (“on-demand”) provisioning of resources on a fine-grained, self-service basis in near real-time[60][61] (Note, the VM startup time varies by VM type, location, OS and cloud providers[60]), without users having to engineer for peak loads.[62][63][64] This gives the ability to scale up when the usage need increases or down if resources are not being used.[65] The time-efficient benefit of cloud scalability also means faster time to market, more business flexibility, and adaptability, as adding new resources does not take as much time as it used to.[66] Emerging approaches for managing elasticity include the use of machine learning techniques to propose efficient elasticity models.[67]

- Security can improve due to centralization of data, increased security-focused resources, etc., but concerns can persist about loss of control over certain sensitive data, and the lack of security for stored kernels. Security is often as good as or better than other traditional systems, in part because service providers are able to devote resources to solving security issues that many customers cannot afford to tackle or which they lack the technical skills to address.[68] However, the complexity of security is greatly increased when data is distributed over a wider area or over a greater number of devices, as well as in multi-tenant systems shared by unrelated users. In addition, user access to security audit logs may be difficult or impossible. Private cloud installations are in part motivated by users’ desire to retain control over the infrastructure and avoid losing control of information security.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology’s definition of cloud computing identifies “five essential characteristics”:

On-demand self-service. A consumer can unilaterally provision computing capabilities, such as server time and network storage, as needed automatically without requiring human interaction with each service provider.

Broad network access. Capabilities are available over the network and accessed through standard mechanisms that promote use by heterogeneous thin or thick client platforms (e.g., mobile phones, tablets, laptops, and workstations).

Resource pooling. The provider’s computing resources are pooled to serve multiple consumers using a multi-tenant model, with different physical and virtual resources dynamically assigned and reassigned according to consumer demand.

Rapid elasticity. Capabilities can be elastically provisioned and released, in some cases automatically, to scale rapidly outward and inward commensurate with demand. To the consumer, the capabilities available for provisioning often appear unlimited and can be appropriated in any quantity at any time.

Measured service. Cloud systems automatically control and optimize resource use by leveraging a metering capability at some level of abstraction appropriate to the type of service (e.g., storage, processing, bandwidth, and active user accounts). Resource usage can be monitored, controlled, and reported, providing transparency for both the provider and consumer of the utilized service.

— National Institute of Standards and Technology[69]

Service models[edit]

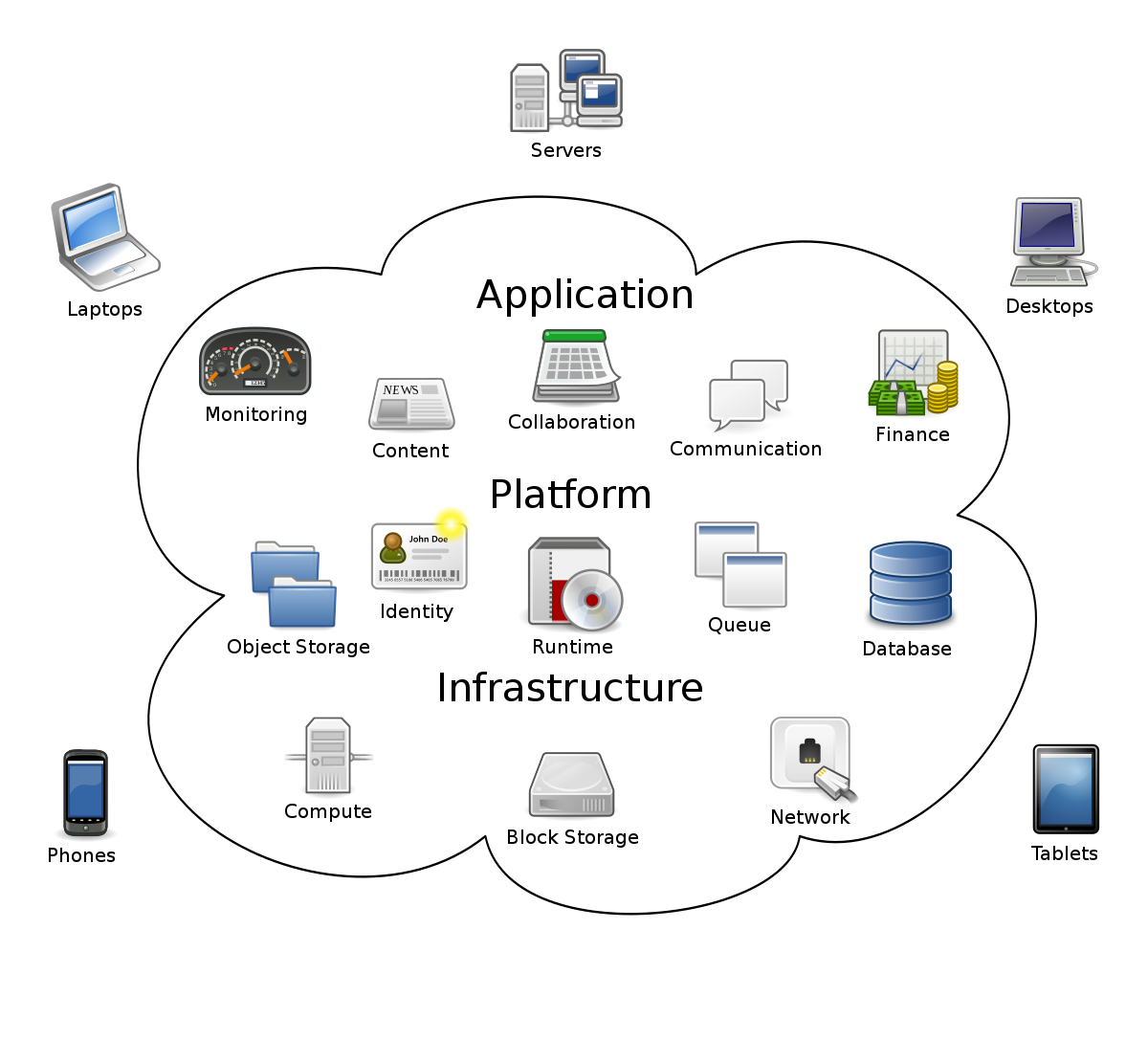

Though service-oriented architecture advocates “Everything as a service” (with the acronyms EaaS or XaaS,[70] or simply aas), cloud-computing providers offer their “services” according to different models, of which the three standard models per NIST are Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a Service (SaaS).[69] These models offer increasing abstraction; they are thus often portrayed as layers in a stack: infrastructure-, platform- and software-as-a-service, but these need not be related. For example, one can provide SaaS implemented on physical machines (bare metal), without using underlying PaaS or IaaS layers, and conversely one can run a program on IaaS and access it directly, without wrapping it as SaaS.

Infrastructure as a service (IaaS)[edit]

“Infrastructure as a service” (IaaS) refers to online services that provide high-level APIs used to abstract various low-level details of underlying network infrastructure like physical computing resources, location, data partitioning, scaling, security, backup, etc. A hypervisor runs the virtual machines as guests. Pools of hypervisors within the cloud operational system can support large numbers of virtual machines and the ability to scale services up and down according to customers’ varying requirements. Linux containers run in isolated partitions of a single Linux kernel running directly on the physical hardware. Linux cgroups and namespaces are the underlying Linux kernel technologies used to isolate, secure and manage the containers. Containerisation offers higher performance than virtualization because there is no hypervisor overhead. IaaS clouds often offer additional resources such as a virtual-machine disk-image library, raw block storage, file or object storage, firewalls, load balancers, IP addresses, virtual local area networks (VLANs), and software bundles.[71]

The NIST’s definition of cloud computing describes IaaS as “where the consumer is able to deploy and run arbitrary software, which can include operating systems and applications. The consumer does not manage or control the underlying cloud infrastructure but has control over operating systems, storage, and deployed applications; and possibly limited control of select networking components (e.g., host firewalls).”[69]

IaaS-cloud providers supply these resources on-demand from their large pools of equipment installed in data centers. For wide-area connectivity, customers can use either the Internet or carrier clouds (dedicated virtual private networks). To deploy their applications, cloud users install operating-system images and their application software on the cloud infrastructure. In this model, the cloud user patches and maintains the operating systems and the application software. Cloud providers typically bill IaaS services on a utility computing basis: cost reflects the number of resources allocated and consumed.[72]

Platform as a service (PaaS)[edit]

The NIST’s definition of cloud computing defines Platform as a Service as:[69]

The capability provided to the consumer is to deploy onto the cloud infrastructure consumer-created or acquired applications created using programming languages, libraries, services, and tools supported by the provider. The consumer does not manage or control the underlying cloud infrastructure including network, servers, operating systems, or storage, but has control over the deployed applications and possibly configuration settings for the application-hosting environment.

PaaS vendors offer a development environment to application developers. The provider typically develops toolkit and standards for development and channels for distribution and payment. In the PaaS models, cloud providers deliver a computing platform, typically including an operating system, programming-language execution environment, database, and the web server. Application developers develop and run their software on a cloud platform instead of directly buying and managing the underlying hardware and software layers. With some PaaS, the underlying computer and storage resources scale automatically to match application demand so that the cloud user does not have to allocate resources manually.[73][need quotation to verify]

Some integration and data management providers also use specialized applications of PaaS as delivery models for data. Examples include iPaaS (Integration Platform as a Service) and dPaaS (Data Platform as a Service). iPaaS enables customers to develop, execute and govern integration flows.[74] Under the iPaaS integration model, customers drive the development and deployment of integrations without installing or managing any hardware or middleware.[75] dPaaS delivers integration—and data-management—products as a fully managed service.[76] Under the dPaaS model, the PaaS provider, not the customer, manages the development and execution of programs by building data applications for the customer. dPaaS users access data through data-visualization tools.[77]

Software as a service (SaaS)[edit]

The NIST’s definition of cloud computing defines Software as a Service as:[69]

The capability provided to the consumer is to use the provider’s applications running on a cloud infrastructure. The applications are accessible from various client devices through either a thin client interface, such as a web browser (e.g., web-based email), or a program interface. The consumer does not manage or control the underlying cloud infrastructure including network, servers, operating systems, storage, or even individual application capabilities, with the possible exception of limited user-specific application configuration settings.

In the software as a service (SaaS) model, users gain access to application software and databases. Cloud providers manage the infrastructure and platforms that run the applications. SaaS is sometimes referred to as “on-demand software” and is usually priced on a pay-per-use basis or using a subscription fee.[78] In the SaaS model, cloud providers install and operate application software in the cloud and cloud users access the software from cloud clients. Cloud users do not manage the cloud infrastructure and platform where the application runs. This eliminates the need to install and run the application on the cloud user’s own computers, which simplifies maintenance and support. Cloud applications differ from other applications in their scalability—which can be achieved by cloning tasks onto multiple virtual machines at run-time to meet changing work demand.[79] Load balancers distribute the work over the set of virtual machines. This process is transparent to the cloud user, who sees only a single access-point. To accommodate a large number of cloud users, cloud applications can be multitenant, meaning that any machine may serve more than one cloud-user organization.

The pricing model for SaaS applications is typically a monthly or yearly flat fee per user,[80] so prices become scalable and adjustable if users are added or removed at any point. It may also be free.[81] Proponents claim that SaaS gives a business the potential to reduce IT operational costs by outsourcing hardware and software maintenance and support to the cloud provider. This enables the business to reallocate IT operations costs away from hardware/software spending and from personnel expenses, towards meeting other goals. In addition, with applications hosted centrally, updates can be released without the need for users to install new software. One drawback of SaaS comes with storing the users’ data on the cloud provider’s server. As a result,[citation needed] there could be unauthorized access to the data.[82] Examples of applications offered as SaaS are games and productivity software like Google Docs and Office Online. SaaS applications may be integrated with cloud storage or File hosting services, which is the case with Google Docs being integrated with Google Drive, and Office Online being integrated with OneDrive.[83]

Mobile “backend” as a service (MBaaS)[edit]

In the mobile “backend” as a service (m) model, also known as backend as a service (BaaS), web app and mobile app developers are provided with a way to link their applications to cloud storage and cloud computing services with application programming interfaces (APIs) exposed to their applications and custom software development kits (SDKs). Services include user management, push notifications, integration with social networking services[84] and more. This is a relatively recent model in cloud computing,[85] with most BaaS startups dating from 2011 or later[86][87][88] but trends indicate that these services are gaining significant mainstream traction with enterprise consumers.[89]

Serverless computing or Function-as-a-Service (FaaS)[edit]

Serverless computing is a cloud computing code execution model in which the cloud provider fully manages starting and stopping virtual machines as necessary to serve requests, and requests are billed by an abstract measure of the resources required to satisfy the request, rather than per virtual machine, per hour.[90] Despite the name, it does not actually involve running code without servers.[90] Serverless computing is so named because the business or person that owns the system does not have to purchase, rent or provide servers or virtual machines for the back-end code to run on.

Function as a service (FaaS) is a service-hosted remote procedure call that leverages serverless computing to enable the deployment of individual functions in the cloud that run in response to events.[91] FaaS is considered by some to come under the umbrella of serverless computing, while some others use the terms interchangeably.[92]

Deployment models[edit]

Private cloud[edit]

Private cloud is cloud infrastructure operated solely for a single organization, whether managed internally or by a third party, and hosted either internally or externally.[69] Undertaking a private cloud project requires significant engagement to virtualize the business environment, and requires the organization to reevaluate decisions about existing resources. It can improve business, but every step in the project raises security issues that must be addressed to prevent serious vulnerabilities. Self-run data centers[93] are generally capital intensive. They have a significant physical footprint, requiring allocations of space, hardware, and environmental controls. These assets have to be refreshed periodically, resulting in additional capital expenditures. They have attracted criticism because users “still have to buy, build, and manage them” and thus do not benefit from less hands-on management,[94] essentially “[lacking] the economic model that makes cloud computing such an intriguing concept”.[95][96]

Public cloud[edit]

Cloud services are considered “public” when they are delivered over the public Internet, and they may be offered as a paid subscription, or free of charge.[97] Architecturally, there are few differences between public- and private-cloud services, but security concerns increase substantially when services (applications, storage, and other resources) are shared by multiple customers. Most public-cloud providers offer direct-connection services that allow customers to securely link their legacy data centers to their cloud-resident applications.[53][98]

Several factors like the functionality of the solutions, cost, integrational and organizational aspects as well as safety & security are influencing the decision of enterprises and organizations to choose a public cloud or on-premises solution.[99]

Hybrid cloud[edit]

Hybrid cloud is a composition of a public cloud and a private environment, such as a private cloud or on-premises resources,[100][101] that remain distinct entities but are bound together, offering the benefits of multiple deployment models. Hybrid cloud can also mean the ability to connect collocation, managed and/or dedicated services with cloud resources.[69] Gartner defines a hybrid cloud service as a cloud computing service that is composed of some combination of private, public and community cloud services, from different service providers.[102] A hybrid cloud service crosses isolation and provider boundaries so that it can’t be simply put in one category of private, public, or community cloud service. It allows one to extend either the capacity or the capability of a cloud service, by aggregation, integration or customization with another cloud service.

Varied use cases for hybrid cloud composition exist. For example, an organization may store sensitive client data in house on a private cloud application, but interconnect that application to a business intelligence application provided on a public cloud as a software service.[103] This example of hybrid cloud extends the capabilities of the enterprise to deliver a specific business service through the addition of externally available public cloud services. Hybrid cloud adoption depends on a number of factors such as data security and compliance requirements, level of control needed over data, and the applications an organization uses.[104]

Another example of hybrid cloud is one where IT organizations use public cloud computing resources to meet temporary capacity needs that can not be met by the private cloud.[105] This capability enables hybrid clouds to employ cloud bursting for scaling across clouds.[69] Cloud bursting is an application deployment model in which an application runs in a private cloud or data center and “bursts” to a public cloud when the demand for computing capacity increases. A primary advantage of cloud bursting and a hybrid cloud model is that an organization pays for extra compute resources only when they are needed.[106] Cloud bursting enables data centers to create an in-house IT infrastructure that supports average workloads, and use cloud resources from public or private clouds, during spikes in processing demands.[107] The specialized model of hybrid cloud, which is built atop heterogeneous hardware, is called “Cross-platform Hybrid Cloud”. A cross-platform hybrid cloud is usually powered by different CPU architectures, for example, x86-64 and ARM, underneath. Users can transparently deploy and scale applications without knowledge of the cloud’s hardware diversity.[108] This kind of cloud emerges from the rise of ARM-based system-on-chip for server-class computing.

Hybrid cloud infrastructure essentially serves to eliminate limitations inherent to the multi-access relay characteristics of private cloud networking. The advantages include enhanced runtime flexibility and adaptive memory processing unique to virtualized interface models.[109]

Others[edit]

[edit]

Community cloud shares infrastructure between several organizations from a specific community with common concerns (security, compliance, jurisdiction, etc.), whether managed internally or by a third-party, and either hosted internally or externally. The costs are spread over fewer users than a public cloud (but more than a private cloud), so only some of the cost savings potential of cloud computing are realized.[69]

Distributed cloud[edit]

A cloud computing platform can be assembled from a distributed set of machines in different locations, connected to a single network or hub service. It is possible to distinguish between two types of distributed clouds: public-resource computing and volunteer cloud.

- Public-resource computing—This type of distributed cloud results from an expansive definition of cloud computing, because they are more akin to distributed computing than cloud computing. Nonetheless, it is considered a sub-class of cloud computing.

- Volunteer cloud—Volunteer cloud computing is characterized as the intersection of public-resource computing and cloud computing, where a cloud computing infrastructure is built using volunteered resources. Many challenges arise from this type of infrastructure, because of the volatility of the resources used to build it and the dynamic environment it operates in. It can also be called peer-to-peer clouds, or ad-hoc clouds. An interesting effort in such direction is Cloud@Home, it aims to implement a cloud computing infrastructure using volunteered resources providing a business-model to incentivize contributions through financial restitution.[110]

Multicloud[edit]

Multicloud is the use of multiple cloud computing services in a single heterogeneous architecture to reduce reliance on single vendors, increase flexibility through choice, mitigate against disasters, etc. It differs from hybrid cloud in that it refers to multiple cloud services, rather than multiple deployment modes (public, private, legacy).[111][112][113]

Poly cloud[edit]

Poly cloud refers to the use of multiple public clouds for the purpose of leveraging specific services that each provider offers. It differs from Multi cloud in that it is not designed to increase flexibility or mitigate against failures but is rather used to allow an organization to achieve more that could be done with a single provider.[114]

Big data cloud[edit]

The issues of transferring large amounts of data to the cloud as well as data security once the data is in the cloud initially hampered adoption of cloud for big data, but now that much data originates in the cloud and with the advent of bare-metal servers, the cloud has become[115] a solution for use cases including business analytics and geospatial analysis.[116]

HPC cloud[edit]

HPC cloud refers to the use of cloud computing services and infrastructure to execute high-performance computing (HPC) applications.[117] These applications consume considerable amount of computing power and memory and are traditionally executed on clusters of computers. In 2016 a handful of companies, including R-HPC, Amazon Web Services, Univa, Silicon Graphics International, Sabalcore, Gomput, and Penguin Computing offered a high performance computing cloud. The Penguin On Demand (POD) cloud was one of the first non-virtualized remote HPC services offered on a pay-as-you-go basis.[118][119] Penguin Computing launched its HPC cloud in 2016 as alternative to Amazon’s EC2 Elastic Compute Cloud, which uses virtualized computing nodes.[120][121]

Architecture[edit]

Cloud architecture,[122] the systems architecture of the software systems involved in the delivery of cloud computing, typically involves multiple cloud components communicating with each other over a loose coupling mechanism such as a messaging queue. Elastic provision implies intelligence in the use of tight or loose coupling as applied to mechanisms such as these and others.

Cloud engineering[edit]

Cloud engineering is the application of engineering disciplines of cloud computing. It brings a systematic approach to the high-level concerns of commercialization, standardization and governance in conceiving, developing, operating and maintaining cloud computing systems. It is a multidisciplinary method encompassing contributions from diverse areas such as systems, software, web, performance, information technology engineering, security, platform, risk, and quality engineering.

Security and privacy[edit]

Cloud computing poses privacy concerns because the service provider can access the data that is in the cloud at any time. It could accidentally or deliberately alter or delete information.[123] Many cloud providers can share information with third parties if necessary for purposes of law and order without a warrant. That is permitted in their privacy policies, which users must agree to before they start using cloud services. Solutions to privacy include policy and legislation as well as end-users’ choices for how data is stored.[123] Users can encrypt data that is processed or stored within the cloud to prevent unauthorized access.[124][123] Identity management systems can also provide practical solutions to privacy concerns in cloud computing. These systems distinguish between authorized and unauthorized users and determine the amount of data that is accessible to each entity.[125] The systems work by creating and describing identities, recording activities, and getting rid of unused identities.

According to the Cloud Security Alliance, the top three threats in the cloud are Insecure Interfaces and APIs, Data Loss & Leakage, and Hardware Failure—which accounted for 29%, 25% and 10% of all cloud security outages respectively. Together, these form shared technology vulnerabilities. In a cloud provider platform being shared by different users, there may be a possibility that information belonging to different customers resides on the same data server. Additionally, Eugene Schultz, chief technology officer at Emagined Security, said that hackers are spending substantial time and effort looking for ways to penetrate the cloud. “There are some real Achilles’ heels in the cloud infrastructure that are making big holes for the bad guys to get into”. Because data from hundreds or thousands of companies can be stored on large cloud servers, hackers can theoretically gain control of huge stores of information through a single attack—a process he called “hyperjacking”. Some examples of this include the Dropbox security breach, and iCloud 2014 leak.[126] Dropbox had been breached in October 2014, having over 7 million of its users passwords stolen by hackers in an effort to get monetary value from it by Bitcoins (BTC). By having these passwords, they are able to read private data as well as have this data be indexed by search engines (making the information public).[126]

There is the problem of legal ownership of the data (If a user stores some data in the cloud, can the cloud provider profit from it?). Many Terms of Service agreements are silent on the question of ownership.[127] Physical control of the computer equipment (private cloud) is more secure than having the equipment off-site and under someone else’s control (public cloud). This delivers great incentive to public cloud computing service providers to prioritize building and maintaining strong management of secure services.[128] Some small businesses that don’t have expertise in IT security could find that it’s more secure for them to use a public cloud. There is the risk that end users do not understand the issues involved when signing on to a cloud service (persons sometimes don’t read the many pages of the terms of service agreement, and just click “Accept” without reading). This is important now that cloud computing is common and required for some services to work, for example for an intelligent personal assistant (Apple’s Siri or Google Assistant). Fundamentally, private cloud is seen as more secure with higher levels of control for the owner, however public cloud is seen to be more flexible and requires less time and money investment from the user.[129]

Limitations and disadvantages[edit]

According to Bruce Schneier, “The downside is that you will have limited customization options. Cloud computing is cheaper because of economics of scale, and—like any outsourced task—you tend to get what you get. A restaurant with a limited menu is cheaper than a personal chef who can cook anything you want. Fewer options at a much cheaper price: it’s a feature, not a bug.” He also suggests that “the cloud provider might not meet your legal needs” and that businesses need to weigh the benefits of cloud computing against the risks.[130]

In cloud computing, the control of the back end infrastructure is limited to the cloud vendor only. Cloud providers often decide on the management policies, which moderates what the cloud users are able to do with their deployment.[131] Cloud users are also limited to the control and management of their applications, data and services.[132] This includes data caps, which are placed on cloud users by the cloud vendor allocating a certain amount of bandwidth for each customer and are often shared among other cloud users.[132]

Privacy and confidentiality are big concerns in some activities. For instance, sworn translators working under the stipulations of an NDA, might face problems regarding sensitive data that are not encrypted.[133] Due to the use of the internet, confidential information such as employee data and user data can be easily available to third-party organisations and people in Cloud Computing.[134]

Cloud computing has some limitations for smaller business operations, particularly regarding security and downtime. Technical outages are inevitable and occur sometimes when cloud service providers (CSPs) become overwhelmed in the process of serving their clients. This may result in temporary business suspension. Since this technology’s systems rely on the Internet, an individual cannot access their applications, server, or data from the cloud during an outage.[135]

Emerging trends[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021)

|

Cloud computing is still a subject of research.[136] A driving factor in the evolution of cloud computing has been chief technology officers seeking to minimize risk of internal outages and mitigate the complexity of housing network and computing hardware in-house.[137] They are also looking to share information to workers located in diverse areas in near and real-time, to enable teams to work seamlessly, no matter where they are located. Since the global pandemic of 2020, cloud technology jumped ahead in popularity due to the level of security of data and the flexibility of working options for all employees, notably remote workers. For example, Zoom grew over 160% in 2020 alone.[138]

Digital forensics in the cloud[edit]

The issue of carrying out investigations where the cloud storage devices cannot be physically accessed has generated a number of changes to the way that digital evidence is located and collected.[139] New process models have been developed to formalize collection.[140]

In some scenarios existing digital forensics tools can be employed to access cloud storage as networked drives (although this is a slow process generating a large amount of internet traffic).[citation needed]

An alternative approach is to deploy a tool that processes in the cloud itself.[141]

For organizations using Office 365 with an ‘E5’ subscription, there is the option to use Microsoft’s built-in e-discovery resources, although these do not provide all the functionality that is typically required for a forensic process.[142]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Ray, Partha Pratim (2018). “An Introduction to Dew Computing: Definition, Concept and Implications – IEEE Journals & Magazine”. IEEE Access. 6: 723–737. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2775042. S2CID 3324933.

- ^ Montazerolghaem, Ahmadreza; Yaghmaee, Mohammad Hossein; Leon-Garcia, Alberto (September 2020). “Green Cloud Multimedia Networking: NFV/SDN Based Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation”. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking. 4 (3): 873–889. doi:10.1109/TGCN.2020.2982821. ISSN 2473-2400. S2CID 216188024.

- ^ “Where’s The Rub: Cloud Computing’s Hidden Costs”. Forbes. 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ^ “What is Cloud Computing?”. Amazon Web Services. 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ^ Baburajan, Rajani (2011-08-24). “The Rising Cloud Storage Market Opportunity Strengthens Vendors”. It.tmcnet.com. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- ^ Oestreich, Ken (2010-11-15). “Converged Infrastructure”. CTO Forum. Thectoforum.com. Archived from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- ^ Ted Simpson, Jason Novak, Hands on Virtual Computing, 2017, ISBN 1337515744, p. 451

- ^ “IDC Forecasts Worldwide “Whole Cloud” Spending to Reach $1.3 Trillion by 2025″. Idc.com. 2021-09-14. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ^ “Gartner Forecasts Worldwide Public Cloud End-User Spending to Reach Nearly $500 Billion in 2022”.

- ^ “Cloud’s trillion-dollar prize is up for grabs”. McKinsey. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ^ “Gartner Says More Than Half of Enterprise IT Spending in Key Market Segments Will Shift to the Cloud by 2025”.

- ^ AT&T (1993). “What Is The Cloud?”. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-10-27. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

You can think of our electronic meeting place as the Cloud. PersonaLink was built from the ground up to give handheld communicators and other devices easy access to a variety of services. […] Telescript is the revolutionary software technology that makes intelligent assistance possible. Invented by General Magic, AT&T is the first company to harness Telescript, and bring its benefits to people everywhere. […] Very shortly, anyone with a computer, a personal communicator, or television will be able to use intelligent assistance in the Cloud. And our new meeting place is open, so that anyone, whether individual, entrepreneur, or a multinational company, will be able to offer information, goods, and services.

- ^ Steven Levy (April 1994). “Bill and Andy’s Excellent Adventure II”. Wired.

- ^ White, J.E. “Network Specifications for Remote Job Entry and Remote Job Output Retrieval at UCSB”. tools.ietf.org. Retrieved 2016-03-21.

- ^ “July, 1993 meeting report from the IP over ATM working group of the IETF”. CH: Switch. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Corbató, Fernando J. “An Experimental Time-Sharing System”. SJCC Proceedings. MIT. Archived from the original on 6 September 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ Levy, Steven (April 1994). “Bill and Andy’s Excellent Adventure II”. Wired.

- ^ Levy, Steven (2014-05-23). “Tech Time Warp of the Week: Watch AT&T Invent Cloud Computing in 1994”. Wired.

AT&T and the film’s director, David Hoffman, pulled out the cloud metaphor–something that had long been used among networking and telecom types. […]

“You can think of our electronic meeting place as the cloud,” says the film’s narrator, […]

David Hoffman, the man who directed the film and shaped all that cloud imagery, was a General Magic employee. - ^ “Announcing Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2) – beta”. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Qian, Ling; Lou, Zhigou; Du, Yujian; Gou, Leitao. “Cloud Computing: An Overview”. researchgate.net. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ “Introducing Google App Engine + our new blog”. Google Developer Blog. 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ “App Engine”. cloud.google.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ “Nebula Cloud Computing Platform: NASA”. Open Government at NASA. 2012-11-20. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ Rochwerger, B.; Breitgand, D.; Levy, E.; Galis, A.; Nagin, K.; Llorente, I. M.; Montero, R.; Wolfsthal, Y.; Elmroth, E.; Caceres, J.; Ben-Yehuda, M.; Emmerich, W.; Galan, F. (2009). “The Reservoir model and architecture for open federated cloud computing”. IBM Journal of Research and Development. 53 (4): 4:1–4:11. doi:10.1147/JRD.2009.5429058.

- ^ Keep an eye on cloud computing, Amy Schurr, Network World, 2008-07-08, citing the Gartner report, “Cloud Computing Confusion Leads to Opportunity”. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- ^ Gartner (2008-08-18). “Gartner Says Worldwide IT Spending on Pace to Surpass Trillion in 2008”. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008.

- ^ “Cluster Exploratory (CluE) nsf08560”. www.nsf.gov.

- ^ “285 millions d’euros pour Andromède, le cloud souverain français – le Monde Informatique”. Archived from the original on 2011-10-23.

- ^ Hicks, Jacqueline. “‘Digital colonialism’: why some countries want to take control of their people’s data from Big Tech”. The Conversation.

- ^ “Orange enterre Cloudwatt, qui fermera ses portes le 31 janvier 2020”. www.nextinpact.com. August 30, 2019.

- ^ “Cloudwatt : Vie et mort du premier ” cloud souverain ” de la France”. 29 August 2019.

- ^ “Windows Azure General Availability”. The Official Microsoft Blog. Microsoft. 2010-02-01. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ^ Milita Datta (August 9, 2016). “Apache CloudStack vs. OpenStack: Which Is the Best?”. DZone · Cloud Zone.

- ^ “OpenNebula vs OpenStack”. SoftwareInsider.[dead link]

- ^ Kostantos, Konstantinos, et al. “OPEN-source IaaS fit for purpose: a comparison between OpenNebula and OpenStack.” International Journal of Electronic Business Management 11.3 (2013)

- ^ L. Albertson, “OpenStack vs. Ganeti”, LinuxFest Northwest 2017

- ^ Qevani, Elton, et al. “What can OpenStack adopt from a Ganeti-based open-source IaaS?.” Cloud Computing (CLOUD), 2014 IEEE 7th International Conference on. IEEE, 2014

- ^ Von Laszewski, Gregor, et al. “Comparison of multiple cloud frameworks.”, IEEE 5th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), 2012.

- ^ Diaz, Javier et al. ” Abstract Image Management and Universal Image Registration for Cloud and HPC Infrastructures “, IEEE 5th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), 2012

- ^ “Launch of IBM Smarter Computing”. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ “Launch of Oracle Cloud”. The Register. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ “Oracle Cloud, Enterprise-Grade Cloud Solutions: SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS”. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ “Larry Ellison Doesn’t Get the Cloud: The Dumbest Idea of 2013”. Forbes.com. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ “Oracle Disrupts Cloud Industry with End-to-End Approach”. Forbes.com. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ “Google Compute Engine is now Generally Available with expanded OS support, transparent maintenance, and lower prices”. Google Developers Blog. 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. “Microsoft developer reveals Linux is now more used on Azure than Windows Server”. ZDNet. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

- ^ “Announcing General Availability of AWS Outposts”. Amazon Web Services, Inc.

- ^ a b c HAMDAQA, Mohammad (2012). Cloud Computing Uncovered: A Research Landscape (PDF). Elsevier Press. pp. 41–85. ISBN 978-0-12-396535-6.

- ^ “Distributed Application Architecture” (PDF). Sun Microsystem. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ Vaquero, Luis M.; Rodero-Merino, Luis; Caceres, Juan; Lindner, Maik (December 2008). “It’s probable that you’ve misunderstood ‘Cloud Computing’ until now”. Sigcomm Comput. Commun. Rev. TechPluto. 39 (1): 50–55. doi:10.1145/1496091.1496100. S2CID 207171174.

- ^ Danielson, Krissi (2008-03-26). “Distinguishing Cloud Computing from Utility Computing”. Ebizq.net. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ “Recession Is Good For Cloud Computing – Microsoft Agrees”. CloudAve. 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ a b c d “Defining ‘Cloud Services’ and “Cloud Computing”“. IDC. 2008-09-23. Archived from the original on 2010-07-22. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ “State of the Art | e-FISCAL project”. www.efiscal.eu.

- ^ Farber, Dan (2008-06-25). “The new geek chic: Data centers”. CNET News. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ “Jeff Bezos’ Risky Bet”. Business Week.

- ^ He, Sijin; Guo, L.; Guo, Y.; Ghanem, M. (June 2012). Improving Resource Utilisation in the Cloud Environment Using Multivariate Probabilistic Models. 2012 2012 IEEE 5th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD). pp. 574–581. doi:10.1109/CLOUD.2012.66. ISBN 978-1-4673-2892-0. S2CID 15374752.

- ^ He, Qiang, et al. “Formulating Cost-Effective Monitoring Strategies for Service-based Systems.” (2013): 1–1.

- ^ King, Rachael (2008-08-04). “Cloud Computing: Small Companies Take Flight”. Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ a b Mao, Ming; M. Humphrey (2012). A Performance Study on the VM Startup Time in the Cloud. Proceedings of 2012 IEEE 5th International Conference on Cloud Computing (Cloud2012). p. 423. doi:10.1109/CLOUD.2012.103. ISBN 978-1-4673-2892-0. S2CID 1285357.

- ^ Bruneo, Dario; Distefano, Salvatore; Longo, Francesco; Puliafito, Antonio; Scarpa, Marco (2013). “Workload-Based Software Rejuvenation in Cloud Systems”. IEEE Transactions on Computers. 62 (6): 1072–1085. doi:10.1109/TC.2013.30. S2CID 23981532.

- ^ Kuperberg, Michael; Herbst, Nikolas; Kistowski, Joakim Von; Reussner, Ralf (2011). “Defining and Measuring Cloud Elasticity”. KIT Software Quality Departement. doi:10.5445/IR/1000023476. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ “Economies of Cloud Scale Infrastructure”. Cloud Slam 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-10-27. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ He, Sijin; L. Guo; Y. Guo; C. Wu; M. Ghanem; R. Han (March 2012). Elastic Application Container: A Lightweight Approach for Cloud Resource Provisioning. 2012 IEEE 26th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications (AINA). pp. 15–22. doi:10.1109/AINA.2012.74. ISBN 978-1-4673-0714-7. S2CID 4863927.

- ^ Marston, Sean; Li, Zhi; Bandyopadhyay, Subhajyoti; Zhang, Juheng; Ghalsasi, Anand (2011-04-01). “Cloud computing – The business perspective”. Decision Support Systems. 51 (1): 176–189. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2010.12.006.

- ^ Why Cloud computing scalability matters for business growth, Symphony Solutions, 2021

- ^ Nouri, Seyed; Han, Li; Srikumar, Venugopal; Wenxia, Guo; MingYun, He; Wenhong, Tian (2019). “Autonomic decentralized elasticity based on a reinforcement learning controller for cloud applications”. Future Generation Computer Systems. 94: 765–780. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.11.049. S2CID 59284268.

- ^ Mills, Elinor (2009-01-27). “Cloud computing security forecast: Clear skies”. CNET News. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Peter Mell; Timothy Grance (September 2011). The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing (Technical report). National Institute of Standards and Technology: U.S. Department of Commerce. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-145. Special publication 800-145.

- ^ Duan, Yucong; Fu, Guohua; Zhou, Nianjun; Sun, Xiaobing; Narendra, Nanjangud; Hu, Bo (2015). “Everything as a Service (XaaS) on the Cloud: Origins, Current and Future Trends”. 2015 IEEE 8th International Conference on Cloud Computing. IEEE. pp. 621–628. doi:10.1109/CLOUD.2015.88. ISBN 978-1-4673-7287-9. S2CID 8201466.

- ^ Amies, Alex; Sluiman, Harm; Tong, Qiang Guo; Liu, Guo Ning (July 2012). “Infrastructure as a Service Cloud Concepts”. Developing and Hosting Applications on the Cloud. IBM Press. ISBN 978-0-13-306684-5.

- ^ “The Cloud, the Crowd, and Public Policy”.

- ^ Boniface, M.; et al. (2010). Platform-as-a-Service Architecture for Real-Time Quality of Service Management in Clouds. 5th International Conference on Internet and Web Applications and Services (ICIW). Barcelona, Spain: IEEE. pp. 155–160. doi:10.1109/ICIW.2010.91.

- ^ “Integration Platform as a Service (iPaaS)”. Gartner IT Glossary. Gartner.

- ^ Gartner; Massimo Pezzini; Paolo Malinverno; Eric Thoo. “Gartner Reference Model for Integration PaaS”. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ Loraine Lawson (3 April 2015). “IT Business Edge”. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Enterprise CIO Forum; Gabriel Lowy. “The Value of Data Platform-as-a-Service (dPaaS)”. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ “Definition of: SaaS”. PC Magazine Encyclopedia. Ziff Davis. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Hamdaqa, Mohammad. A Reference Model for Developing Cloud Applications (PDF).

- ^ Chou, Timothy. Introduction to Cloud Computing: Business & Technology.

- ^ “HVD: the cloud’s silver lining” (PDF). Intrinsic Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Sun, Yunchuan; Zhang, Junsheng; Xiong, Yongping; Zhu, Guangyu (2014-07-01). “Data Security and Privacy in Cloud Computing”. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks. 10 (7): 190903. doi:10.1155/2014/190903. ISSN 1550-1477. S2CID 13213544.

- ^ “Use OneDrive with Office”. support.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

- ^ Carney, Michael (2013-06-24). “AnyPresence partners with Heroku to beef up its enterprise mBaaS offering”. PandoDaily. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Alex Williams (11 October 2012). “Kii Cloud Opens Doors For Mobile Developer Platform With 25 Million End Users”. TechCrunch. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Aaron Tan (30 September 2012). “FatFractal ups the ante in backend-as-a-service market”. Techgoondu.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Dan Rowinski (9 November 2011). “Mobile Backend As A Service Parse Raises $5.5 Million in Series A Funding”. ReadWrite. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ Pankaj Mishra (7 January 2014). “MobStac Raises $2 Million in Series B To Help Brands Leverage Mobile Commerce”. TechCrunch. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ “built.io Is Building an Enterprise MBaas Platform for IoT”. programmableweb. 2014-03-03. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b Miller, Ron (24 Nov 2015). “AWS Lambda Makes Serverless Applications A Reality”. TechCrunch. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ “bliki: Serverless”. martinfowler.com. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Sbarski, Peter (2017-05-04). Serverless Architectures on AWS: With examples using AWS Lambda (1st ed.). Manning Publications. ISBN 9781617293825.

- ^ “Self-Run Private Cloud Computing Solution – GovConnection”. govconnection.com. 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ^ “Private Clouds Take Shape – Services – Business services – Informationweek”. 2012-09-09. Archived from the original on 2012-09-09.

- ^ Haff, Gordon (2009-01-27). “Just don’t call them private clouds”. CNET News. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ “There’s No Such Thing As A Private Cloud – Cloud-computing -“. 2013-01-26. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26.

- ^ Rouse, Margaret. “What is public cloud?”. Definition from Whatis.com. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ “FastConnect | Oracle Cloud Infrastructure”. cloud.oracle.com. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ^ Schmidt, Rainer; Möhring, Michael; Keller, Barbara (2017). “Customer Relationship Management in a Public Cloud environment – Key influencing factors for European enterprises”. HICSS. Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (2017). doi:10.24251/HICSS.2017.513. hdl:10125/41673. ISBN 9780998133102.

- ^ “What is hybrid cloud? – Definition from WhatIs.com”. SearchCloudComputing. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- ^ Butler, Brandon (2017-10-17). “What is hybrid cloud computing? The benefits of mixing private and public cloud services”. Network World. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- ^ “Mind the Gap: Here Comes Hybrid Cloud – Thomas Bittman”. Thomas Bittman. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ “Business Intelligence Takes to Cloud for Small Businesses”. CIO.com. 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ Désiré Athow (24 August 2014). “Hybrid cloud: is it right for your business?”. TechRadar. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Metzler, Jim; Taylor, Steve. (2010-08-23) “Cloud computing: Reality vs. fiction”, Network World.

- ^ Rouse, Margaret. “Definition: Cloudbursting”, May 2011. SearchCloudComputing.com.

- ^ “How Cloudbursting “Rightsizes” the Data Center”. 2012-06-22.

- ^ Kaewkasi, Chanwit (3 May 2015). “Cross-Platform Hybrid Cloud with Docker”.

- ^ Qiang, Li (2009). “Adaptive management of virtualized resources in cloud computing using feedback control”. First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering.

- ^ Cunsolo, Vincenzo D.; Distefano, Salvatore; Puliafito, Antonio; Scarpa, Marco (2009). “Volunteer Computing and Desktop Cloud: The Cloud@Home Paradigm”. 2009 Eighth IEEE International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications. pp. 134–139. doi:10.1109/NCA.2009.41. S2CID 15848602.

- ^ Rouse, Margaret. “What is a multi-cloud strategy”. SearchCloudApplications. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ King, Rachel. “Pivotal’s head of products: We’re moving to a multi-cloud world”. ZDnet. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Multcloud manage multiple cloud accounts. Retrieved on 06 August 2014

- ^ Gall, Richard (2018-05-16). “Polycloud: a better alternative to cloud agnosticism”. Packt Hub. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Roh, Lucas (31 August 2016). “Is the Cloud Finally Ready for Big Data?”. dataconomy.com. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Yang, C.; Huang, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, K.; Hu, F. (2017). “Big Data and cloud computing: innovation opportunities and challenges”. International Journal of Digital Earth. 10 (1): 13–53. Bibcode:2017IJDE…10…13Y. doi:10.1080/17538947.2016.1239771. S2CID 8053067.

- ^ Netto, M.; Calheiros, R.; Rodrigues, E.; Cunha, R.; Buyya, R. (2018). “HPC Cloud for Scientific and Business Applications: Taxonomy, Vision, and Research Challenges”. ACM Computing Surveys. 51 (1): 8:1–8:29. arXiv:1710.08731. doi:10.1145/3150224. S2CID 3604131.

- ^ Eadline, Douglas. “Moving HPC to the Cloud”. Admin Magazine. Admin Magazine. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ “Penguin Computing On Demand (POD)”. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Niccolai, James (11 August 2009). “Penguin Puts High-performance Computing in the Cloud”. PCWorld. IDG Consumer & SMB. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ “HPC in AWS”. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ “Building GrepTheWeb in the Cloud, Part 1: Cloud Architectures”. Developer.amazonwebservices.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Mark D. “Cloud Computing Privacy Concerns on Our Doorstep”. cacm.acm.org.

- ^ Haghighat, Mohammad; Zonouz, Saman; Abdel-Mottaleb, Mohamed (2015). “CloudID: Trustworthy cloud-based and cross-enterprise biometric identification”. Expert Systems with Applications. 42 (21): 7905–7916. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2015.06.025.

- ^ Indu, I.; Anand, P.M. Rubesh; Bhaskar, Vidhyacharan (August 1, 2018). “Identity and access management in cloud environment: Mechanisms and challenges”. Engineering Science and Technology. 21 (4): 574–588. doi:10.1016/j.jestch.2018.05.010 – via www.sciencedirect.com.

- ^ a b “Google Drive, Dropbox, Box and iCloud Reach the Top 5 Cloud Storage Security Breaches List”. psg.hitachi-solutions.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ^ Maltais, Michelle (26 April 2012). “Who owns your stuff in the cloud?”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ^ “Security of virtualization, cloud computing divides IT and security pros”. Network World. 2010-02-22. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ “The Bumpy Road to Private Clouds”. 2010-12-20. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ “Should Companies Do Most of Their Computing in the Cloud? (Part 1) – Schneier on Security”. www.schneier.com. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ^ “Disadvantages of Cloud Computing (Part 1) – Limited control and flexibility”. www.cloudacademy.com. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ a b “The real limits of cloud computing”. www.itworld.com. 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ Karra, Maria. “Cloud solutions for translation, yes or no?”. IAPTI.org. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Pradhan, Sayam (2021). “Cloud Computing”. Transitioning from Traditional Data Centers to Cloud Computing: Pros and Cons (1 ed.). India. p. 14. ISBN 9798528758633.

- ^ Seltzer, Larry. “Your infrastructure’s in the cloud and the Internet goes down. Now, what?”. ZDNet. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- ^ Smith, David Mitchell. “Hype Cycle for Cloud Computing, 2013”. Gartner. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ “The evolution of Cloud Computing”. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ “Remote work helps Zoom grow 169% in one year, posting $328.2M in Q1 revenue”. TechCrunch. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ Ruan, Keyun; Carthy, Joe; Kechadi, Tahar; Crosbie, Mark (2011-01-01). Cloud forensics: An overview.

- ^ R., Adams (2013). The emergence of cloud storage and the need for a new digital forensic process model. researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au. ISBN 9781466626621. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- ^ Richard, Adams; Graham, Mann; Valerie, Hobbs (2017). “ISEEK, a tool for high speed, concurrent, distributed forensic data acquisition”. Research Online. doi:10.4225/75/5a838d3b1d27f.

- ^ “Office 365 Advanced eDiscovery”. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

Further reading[edit]

- Millard, Christopher (2013). Cloud Computing Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967168-7.

- Weisser, Alexander (2020). International Taxation of Cloud Computing. Editions Juridiques Libres, ISBN 978-2-88954-030-3.

- Singh, Jatinder; Powles, Julia; Pasquier, Thomas; Bacon, Jean (July 2015). “Data Flow Management and Compliance in Cloud Computing”. IEEE Cloud Computing. 2 (4): 24–32. doi:10.1109/MCC.2015.69. S2CID 9812531.

- Armbrust, Michael; Stoica, Ion; Zaharia, Matei; Fox, Armando; Griffith, Rean; Joseph, Anthony D.; Katz, Randy; Konwinski, Andy; Lee, Gunho; Patterson, David; Rabkin, Ariel (1 April 2010). “A view of cloud computing”. Communications of the ACM. 53 (4): 50. doi:10.1145/1721654.1721672. S2CID 1673644.

- Hu, Tung-Hui (2015). A Prehistory of the Cloud. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02951-3.

- Mell, P. (2011, September 31). The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing. Retrieved November 1, 2015, from National Institute of Standards and Technology website

External links[edit]

[ad_2]

Source link